International Symposium Language and consciousness

Varna, Sept. 12-15 1995

Lacan distinguishes three registers which structure human subjectivity: the Imaginary and the Symbolic linked by the Real.

The real dimension can be approached but never reached -it is unattainable-, while the symbolic one is closely connected to language code.

The concept of objet a belongs to the imaginary level while the Autre pertains to the symbolic one and we can find traces of each of them in certain linguistic facts. I intend to illustrate this on the basis of french data, inevitably reducing such a fundamental concept that Lacan considered it from numerous points of view.

Thus, we may look in vain for a strict definition of the objet a; throughout Lacan's work, we meet a multitude of references to it: as a partial object, representation of the absent object (the bobbin of the "fort-da" play[1]), image of beneficial objects[2] and even assimilated to one's look as opposed to one's eye[3]. It represents also the desired object and the cause of desire but, above all, it is a topological entity,[4] separated from the subject though indispensable to its constitution[5].

Nevertheless, since our position is not the one of a psychoanalyst attempting to explore exhaustively the notion but the one of a linguist identifying in linguistic material concordances with some of Lacan's main distinctions, I shall elaborate upon only one typical characteristic of the notion.

Indeed, from his cross-cap topology, Lacan draws up a specific feature of the objet a that is its lack of specularity[6], in other terms: this object does not generate any image, it has no image.

This characteristic deserves our interest because, quite specific to the concept, obvious tokens of it can be found in certain linguistic mechanisms.

By questioning the very notion of "otherness", we set up the enunciative frame within which a speaker says je to an adressee, denoted by tu ; il n'y a d'"autre" qu'entre nous (there is no "other" but between us). The other one about whom je and tu can talk about in his absence is, linguistically, introduced by il . We obtain then, a deictic or anaphoric referential pronoun (here limited to the person).

It is well known that the same pronominal form can fill in the mere syntactic subject function in so-called "impersonal" uses with some verbs which hardly accept other subjects, e.g. : il pleut, il grêle, il neige etc... and also in sentences like : il arrive des tas de choses quand il ne se passe rien or il vaut mieux respecter les usages comme il convient, etc...where the verbs match with any substantive subjects.

By now, the object being our preoccupation, we shall examine later these cases that, here, only exemplify what a dummy form, an holdall form is il. But it is worth noticing that their common denominator is the lack of morphological gender alternance whereas it characterizes referential pronoun. When the pronoun concerns persons, the gender markers correspond to the sexual division.

Coming back to our enunciative situation, it is patent that the subject form assumes the object status for and from both je and tu without any change.

Whereas, in the dialogue,je and tu forms alternate, il or elle remains unchanged between them, regardless of whom is speaking.

Considering henceforth je as the subject[7], the comparison between the french reflexive constructions with the non-reflexive ones, emphasizes the formal specificities of the third personal pronoun in its object syntactic function.

A simple glance at the morphological paradigm, reveals the formal singularity of the third person pronoun as apposed to the two first ones, as shown here:

Direct Object Complement : me

(DOC) te

le/la

Indirect Object Complement :me

(IOC) te

lui

We observe that where me and te remain the same whatever the kind of object function they fulfill, the third person pronoun turns into the nominal articles in the case of DOC and into the unique lui when in IOC function.

Taking into account the se marker as the "reflexive" specifier it is supposed to be, we can compare the respective constructions:

DOC :

je me + Verb = tu te + V = il/elle se + V

je te - = tu me - = il/elle me -

" le/la - = " le/la - = " te -

Simplifying :

DOC :

je me - = tu te -

je te - = tu me -

je me - = il se - tu te - = il se -

je le/la - = il me - tu le/la - = il te -

IOC :

je me - = tu te -

je te - = tu me -

je me - = il se - tu te - = il se -

je lui- = il me - tu lui - = il te -

It is clear that, whatever the case, we always have :

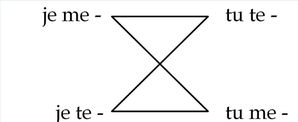

je me - = tu te -

je te - = tu me -

with possibility of substituting the terms of the equations that are, conversely, interexchangeable, as in a mirror, so that we can draw :

This layout fits nicely with the Lacan’s schema of intersubjective dialectic structure. It is the well-known classical schema L of which I give the two versions[8] :

What Lacan wants to bring out is that the subject being S[9], the other one, the real other one (l'Autre) can only be seen through the mirror form (the specular form) of himself (l'autre)[10]. He states that the ego is an imaginary construction unable to catch the other one but under a converse image of himself to the one he identifies with. It is what Lacan calls the subject's alienation into the ego (of the Je into the Moi, of the I into the Me), which is outcome from his division (from the subject's division)[11].

However, there are in language, many traces of this Other one as I shall try to point out next.

Still comparing reflexive constructions to non-reflexive ones and in respect to semantic interpretation, interesting information can be gathered that I shall present successively :

1) Case of syntaxico-semantic symmetry

je me lave / je te lave[12]

je m'habille / je t'habille

je me coiffe / je te coiffe...

This occurs when the verbal action applies to the body object.

As soon as the verb outpaces the limits of the body (of the "corps propre"), a semantic dissymmetry is most likely to arise.

2) Cases of syntaxico-semantic dissymmetry :

a) je m'amuse / je t'amuse

je m'ennuie / je t'ennuie

je me dérange / je te dérange...

For this series of verbs, the semantic dissymmetry is due to a difference in the subject function. In the reflexive construction, the syntactic subject does not coincide with the actant which stands out of the verbal process. Who is responsible for my entertainment, my boredom, my disturbance? The other one, the other ones, somebody who remains nameless.

As about the Other one (l'Autre) Lacan evokes the true subject, the authentic one[13], we are not far from this entity.

Let us consider other examples of dissymetry, quite akin to the preceeding ones :

b) je me renseigne / je te renseigne

je m'informe / je t'informe

je m'instruis / je t'instruis...

In this group of verbs and again in the reflexive use, the syntactic subject is not as passive than in the former case but it acts in another way than it does in the non- reflexive construction. While it is je that gives the information, the instruction, the initiation to te, in the reflexive use, je goes to fetch the information elsewhere.

Who is the one who knows ? In the sixties, Lacan introduced the notion of the "sujet supposé savoir”(the subject supposed to know)[14].

Without going into further details, we have here quite convincing evidence of what Lacan meant[15]. The correspondance with the Autre is quite conclusive and, again, this mysterious entity stands unspoken, brought up by discourse, created by it but never mentioned by the speakers.

The purpose here is not to enumerate all the dissymetric figures -there are many more[16]-, but to locate some linguistic consequences of the subject's division that is the analytical aspect Lacan insists upon. The main point to be underlined here is that the differentiation between the two compared constructions results from a constant process as evidenced by the more colloquial verbal expressions and their continous creativity, for e.g. :

je me plante / je te plante

je me débine / je te débine

je me défonce / je te défonce[17]...

It remains to be examined the proper function of the "reflexivity" marker se when it does not come with a referential pronoun.

It can go with the impersonal pronoun like in : il se trouve (que...), il se peut (que...), comme il se doit etc...or il se passe des choses inédites etc...

What kind of "reflexivity" is this? What se is it supposed to "reflect»?

In the latter example, the sentence can be converted into des choses inédites se passent without any notable semantic modification. The pronoun refering to the effective syntactic subject removes it to the object one, takes its place and hides it, as a subject, at the same time.

On the other hand, semantically speaking, it is clear that the "things" hardly able to act by themselves, the real actant stays unnamed, imprecise, diffuse but omnipresent.

From a grammatical point of view, as the verb passer admits any substantive subjects, the anteposition of se sets the expression into a fixed locution and the same occurs with trouver, pouvoir and devoir in the examples given above.

Furthermore, in such sentences as : le café se boit chaud, les lentilles se mangent en salade etc..., we identify comparable constructions. At the syntacic subject place appear the objects complements, the actant being absent will thus be supplied by on, everybody, the social consensus.

Is it not a singular manner for which to state the social suitability, to invoke the cultural fitness, to edict what correctness is? Expression of the Norm but without really saying it!

Now, in such examples as: la maison se dégrade, le fer se dilate etc..., linguists easily resort to the pragmatic dimension, refering to an empirical knowledge shared by the speakers. In our examples, this is equivalent to mentioning effects without taking their cause into account. The speakers are supposed to re-establish that time itself incurs damage, that heat provokes metal dilatation etc...

This way of expressing effects without causes is proper to language possibility (it has no equivalent in the physical world), that is why it is connected with the Other one, the nameless, unspoken one but coined into language because of its (of his?) absolute necessity for discourse interpretation.

Beyond these remarks, we can repeat the question: what function does se play? Does it reflect anything or is it a false reflector, something like a spectacle frame without lenses? Further, when it becomes undisputed that the presence of se exempts us from mentioning the syntactic subject, exhibiting the object at its place, it allows us to establish that se obliterates the subject, blots it out.

Given that, in our perspective, to analyze se as the "reflexive" specifier turns into a misinterpretation, to an untruth.

Refering again to the enunciation, while me and te remain the grammatical complement forms which alternate -like je and tu respectively- in order to indicate for the third person pronoun, the potential coincidence between the syntactic subject and object (namely, the "coreference") we needed some linguistic marker. Se plays this role, but what is going on then, what is exactly the role ? Se literally swallows the subject which, thus, vanishes. At least this is how we can understand Lacan’s formulation that the objet a lacks specularity, has no-one to identify with, has no imago. [18]. Born from the imagination of je and tu, created between them and for their own dialogue, the objet a has no existence out of the intersubjective boundaries.

As regarding the Other, Lacan says that there is no "Other of the Other" ("Il n'y a pas d'Autre de l'Autre")[19] and this does seem to contradict our observations. In the previously quoted cross-cap topology, Lacan adds up the "trou noir" (black hole) and I do not know yet if it can be superimposed to the se-form, even if they are mutually related. In any case, I take care not to say that this is or is not the objet a or the Autre but only that there are between these entities and linguistic data such concordances that they can hardly be attributed to chance.

Besides, being the speaking subject, "le parlêtre", Lacan’s main field of interest, these concordances are not so unexpected. The psychoanalyst was too much involved in linguistic matters. Considering them from his own standpoint, he met the enunciative specificity shedding some original light on the problems that concern us.

Bibliographical references

- M. Borch-Jacobsen, 1990, Lacan, Le maître absolu, Paris, Flammarion, coll. Champs, 1995.

- J. Dor, 1985 & 1992, Introduction à la lecture de Lacan, Paris, Denoël, coll. "L'espace analytique".

-vol. 1, L'inconscient structuré comme un langage.

-vol. 2, La structure du sujet.

- S. Freud, 1920, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Standard Edition, XVIII.

- J. Lacan,

1954-55, Le moi dans la théorie de Freud et dans la technique de lapsychanalyse, Le Séminaire, Livre II, Paris, Seuil, coll. "Le champ freudien",1973.

1961-62, L'identification, séminaire inédit,

1963-64, Les quatre concepts fondamentaux de la psychanalyse, Le Séminaire, Livre XI, Paris, Seuil, coll. "Points", 1973.

1966, Ecrits, Paris, Seuil, coll. "Le champ freudien".

1968-69, D'un autre à l'Autre, séminaire inédit

1972-73, Encore, Le Séminaire, Livre XX, Paris, Seuil, 1975,

1973, "L'Etourdit" in Scilicet 4, Paris, Seuil, pp. 26-44.

For the major concepts translation :

- J. Lacan, Ecrits, A selection, translated by Alan Sheridan, London, Tavistock Publicat., 1977, 338p.

- J. D. Nasio, 1987, Les yeux de Laure, Le concet d'objet a dans la théorie de J. Lacan, Paris, Aubier, coll. "La psychanalyse prise au mot".

Example sheet

-Syntaxico-semantic symmetry :

je me lave / je te lave

je me lève / je te lève

je m'assieds / je t'assieds

je me promène / je te promène

je me vois / je te vois

je me plais / je te plais...

-Syntaxico-semantic dissymmetry :

a) je m'amuse / je t'amuse

je me distrais / je te distrais

je me réjouis / je te réjouis

je me trahis / je te trahis

je me trompe / je te trompe...

b) je me renseigne / je te renseigne

je m'initie / je t'initie

je m'excuse / je t'excuse

je m'écoute / je t'écoute

je me plains / je te plains...

c) je m'exprime / je t'exprime (+ DOC)

je me redis / je te redis (+ DOC)

je me réserve / je te réserve (+ DOC)

je me rappelle (+ DOC) / je te rappelle (by phone)

je me concentre / --

je me disperse / --

je m'éparpille / --...

d) colloquial expressions :

je me régale / je te régale (= non colloquial)

je m'éclate / je t'éclate

je me barre / je te barre

je me tire / je te tire (+ DOC)...

[1] Reference to Freud's article, 1920, Beyond the Pleasure Principle".

Game based upon repetition of the appearing and disappearing of a bobbin-toy which lays Freud to introduce the pulsion of death.

Lacan will evolve the same illustration in his own manner, notably in Les quatre concepts fondamentaux....

[2] For ex.: the breast, excrement, the sight and the voice. See, in particular, M. Borch-Jacobsen, p. 275.

[3] Cf. Les quatre concepts fondamentaux ... . chap. XX, En toi plus que toi, p. 303.

[4] Topology = Part of the geometry which studies the qualitative properties and relative positions of the geometric beings, independently from their forms and size. First called : situation geometry or analysis situs.

[5] For all this part, see also M. Borch-Jacobsen, pp. 274-282.

[6] Cf. J. Lacan, L'identification, ; D'un autre à l'Autre ; Ecrits, pp. 366-367 & pp.553-554 (note) ; Les quatre concepts fondamentaux ... p. 143 ; "L'Etourdit" .

[7] The question of the subject being another main theoretical Lacan's theme.

[8] Cf. Le moi dans la théorie de Freud ..., chap. XIX, Introduction du grand Autre, p. 284 ; "Séminaire sur la lettre volée", in Ecrits, p. 53 & "D'une question préliminaire à tout traitement possible de la psychose", in Ecrits, p. 548.

J. Dor gives a good explanation of these schemas. cf. vol. 2, IIIème partie, pp. 202-227.

[9] (Es) comes from Freud's formulation : "Wo Es war, soll Ich werden" and represents the subject that is not a totality, cf. Le moi dans la théorie de Freud..., p. 288.

[10] None of them appearing in my own diagram, as is normal.

[11] For a best comprehension of the consequences of this phenomenon, see particularly :Le moi dans la théorie de Freud..., p. 284-288.

[12] For greater clarity, only the two first persons are presented.

[13] About this point and in addition to the yet quoted Lacan's references, cf. J. Dor, vol. 1, pp. 158-165.

[14] Cf. L'identification, 22 nov. 1961 ; D'un autre à l'Autre, 27 nov. 1968 and from the one of the 22 jan. 1969, this formulation that should be analyzed : "Si ce a, ai-je dit... est ce qui conditionne la distinction du je comme soutenant ce champ de l'Autre et pouvant se totaliser comme champ du savoir, (ce qu'il importe de savoir, précisément, c'est qu'à se totaliser ainsi, il n'atteindra jamais au champ de sa suffisance qui s'articule dans le thème hégélien du Selbstbewusstsein).".

See also M. Borch-Jacobsen, pp. 17-25 and J. Dor, vol. 2, pp. 79-80.

[15] "...qu'est-ce qui sait ? Se rend-on compte que c'est l'Autre ? ", Encore, chap. VIII, Le savoir et la vérité, p. 88.

[16] Only figure, here, minimal sentences but if we consider larger syntactic structures, various dissymmetries would appear like : je m'exprime / je t'exprime + DOC ; je me répète / je te répète + DOC etc...

[17] As previously precised, structural dissymmetric cases are not presented, e.g. : je me tire //je te tire + DOC ; je m'appuie + DOC / je t'appuie etc...

[18] "Nous appelons cet être qui n'a plus d'image parce qu'il est fondu en elle, un être non spéculaire.", J. D. Nasio, p. 217.

[19] For a comment of this formulation, see J. Dor, vol. 2, p. 118 (note 21).

commenter cet article …